Insights of a DEPP learning seminar in Goma, DRC By Jean-Louis Lambeau (Learning Advisor - DRC, Kenya and Mozambique)

Is collaboration a good question?

Coordination certainly is a form of collaboration, and it has massively shaped humanitarian mechanisms around the world. But is coordination enough? Given the growing diversity of situations, cultures, institutions and expertise at play, the way people and organisations work together appears today as the magic factor. The one available leverage to push the system’s gravity centre closer to local populations, and to increase unity, density and legitimacy of humanitarian work from the civil society perspective. The question is worth a deeper look. We need concrete evidence and clear mechanisms.

Let’s dig the DEPP

The Disasters Emergency Preparedness Programme (DEPP) is an experimental programme meant to learn about what we call “collaborative advantage”. What it exactly means is not yet clear as we are still at the stammering stages of that learning journey, but it certainly drives us to deepen some key managerial and ethical issues related to “capacities” and “collaboration” applied to humanitarian work.

The DEPP environment is a heterogeneous assembly of humanitarian projects. Work streams are managed internationally by a variety of non-governmental organisations belonging to Start Network and CDAC Network, and implemented by a number of local or international actors in about 10 countries and four continents.

Learning streams are embedded in projects and in specific teamwork such as the Harvard evaluation team and the MEL (monitoring, evaluation and learning) team. It is a chaotic universe that offers many opportunities to produce innovative knowledge, if indeed we manage to dig deep. If we are allowed to open the Pandora box of all contradictions, frustrations, blind spots, failures and paradoxes, we will talk differently of success. Where to start to gather substantive evidence to support this research? Getting together is definitely the first answer.

Now, we are in Goma, DRC

One big room in a hotel by the airport, facing Nyiragongo, the volcano in Goma, Kivu, DRC. There, a highly vulnerable population has been enduring for years massive and recurrent disasters (natural and man-made) in the context of a failing state in a volatile region. Here, the humanitarian system, one of the oldest in place, is omnipresent and ready to last. Here, people speak French, Lingala or Swahili, but rarely, English.

Most of our local DEPP partners have gathered, together with some projects managers and United Nations actors. There are five DEPP projects in the DRC, but this is not the central topic of the day. In fact we will hardly talk about projects, programmes, objectives or time frames: we are here to hear and learn openly about collaboration and capacities in the humanitarian sector from the perspective of the actors present in this room. Institutional actors, UN especially, are a bit puzzled at first by the approach, but they play along nicely.

Arrows and tweets, drawing lines into words

A DaZiBao or giant wallpaper, to visualize connections and capacities of actors and institutions is present in the room. Lots of energy followed by standing debates. Slowly emerging, the portrait of the ghost we hunt. Previous interviews with DEPP project managers and UN representatives had paved the way to structure the initial steps of a collective reflection. Simultaneously, a virtual conversation happened on Twitter thanks to the MEL team in London, building more motivation and interest.

Insights

- - Tools - Networks follow complex streams and capacities present intricate layers that a simple drawing cannot capture: adequate and elaborate tools are available and necessary (such as social media mapping tools).

- - Environments - Capacity by itself is not enough. Enabling environments and resources are necessary to express them concretely. That includes psychological, political and organizational environments.

- - Blind spots - There is a wealth of raw capacities available locally. However it is rarely solicited.

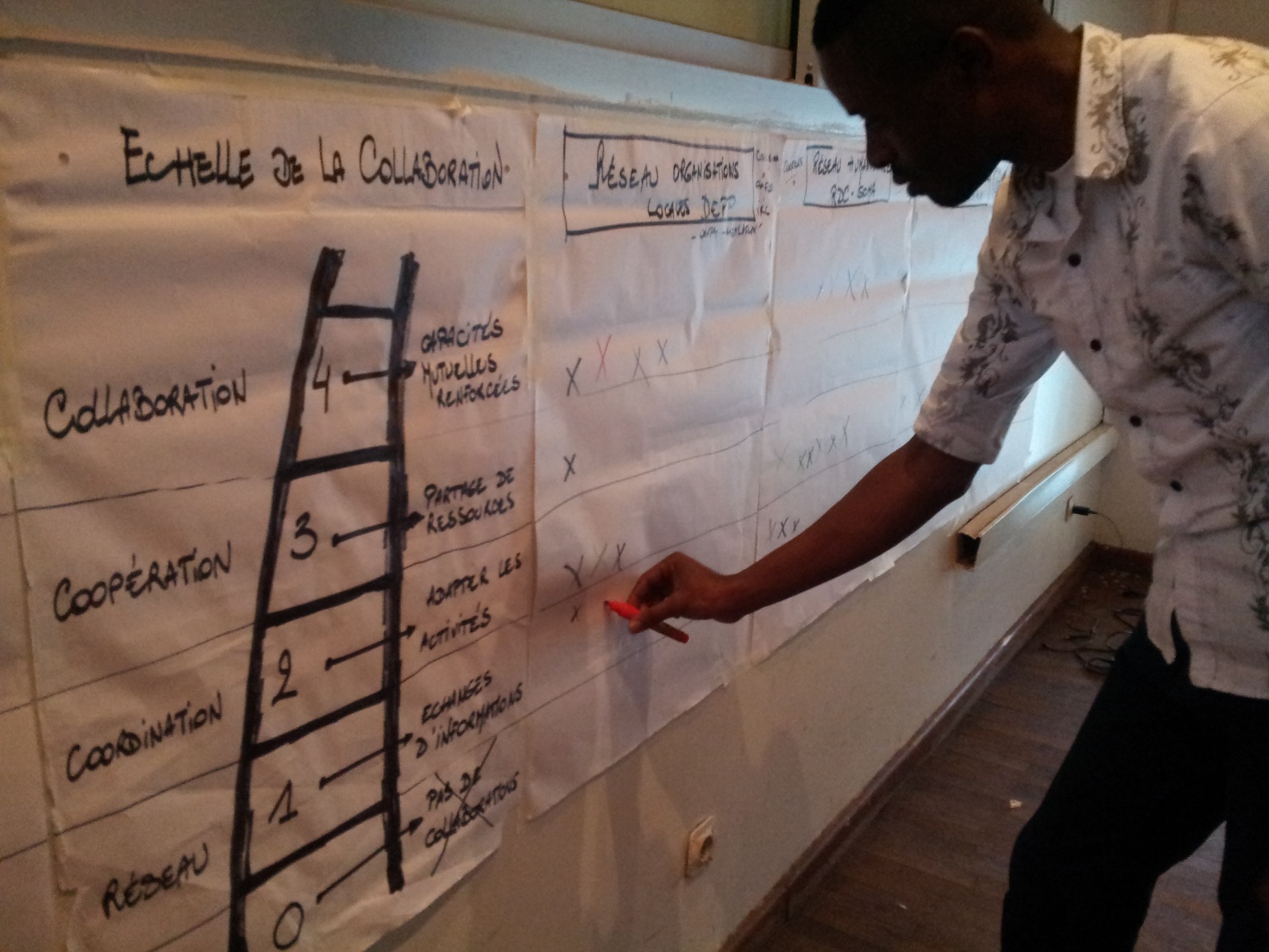

Climbing the collaborative ladder (picture):

The group is invited to characterize different humanitarian settings following the five steps of a ladder (inspired by Himmeman, 2002, and R.Hart, 1997) indicating growing intensities of collaboration:

- Level 0: an absence of collaboration

- Level 1 : networking, exchanging information

- Level 2 : coordination, adapting activities

- Level 3 : cooperation, sharing resources

- Level 4 : strengthening capacities mutually, the ideal situation

The collaborative ladder exercise aims at:

- making sense collectively of the core notion of collaboration,

- reflecting in that light the concrete experience of local networks, teams and partnerships,

- indicating potentials for progression, and in the longer run, monitoring those progressions,

- opening a debate on the processes at play.

Insights:

What are the winning capacities to survive in the humanitarian system?

- - On the ladder, the humanitarian cluster system is noted on level 2 (coordination) with a few hits at level 4. This contradiction triggered a hot debate on the relations between the local civil society the humanitarian system, and the occurrence of disasters.

- - Is it possible that after decades of presence in the country and in the region, the humanitarian system is now part of the problem and plays unwillingly a role in the persistent cycle of violence that justifies its presence?

- - Beyond the obvious necessity of international support, frustrations were expressed in relation to the negative effects of massive in-flow of resources locally, creating disparities felt as unfair.

- - Another frustration is the de-legitimization of local actors often substituted by international ones.

At a certain point it became clear that there was somewhere a red line, a divide between those who are in and those who are out: between those who, identified as capable and well positioned on the mapping, will gain access to the humanitarian resources - and the others who will be limited to a role of information provider.

Capacity, expressed in the terms of the system, is therefore a marker of both integration and exclusion, and a divisive factor locally.

Are projects good collaborative models in the wider humanitarian context?

- - Project’s collaborative dynamics are felt as often short-term, uneven and unstable. It takes time to build trust and mutual understanding locally, but high turnovers and overwork – INGOs usual suspects - are in that sense counterproductive. No doubt that there is a lot more to learn about collaborative (dis)advantages of what remains the most common management model of humanitarian resources. But today the word is with local partners.

Local organizations, best potential for progression

- - Beyond projects, services – and therefore capacities - are markers of the identity and vocation of the local organizations providing them. They are usually interconnected with other local entities (network, level 1) with peaks of collaboration up to level 3 (cooperation) indicating a strong margin for progression.

- - Local organizations should rise to the challenge, and emulate international NGOs and “big players” to access available resources. But the system should also be able to acknowledge and value local capacities in their own rights - as they form eventually the ground for sustainable resilience to disasters.

What about the DEPP?

- - It is recognized that the DEPP bears important collaborative and learning potential, but this yet remains an elusive reality. Specific communication tools (such as the Slack), and specific moments (such as this learning workshop) are necessary to boost the emerging collaborative dynamics in-Country.

Where it really works: with the local communities

- - Unanimously, the highest level of collaboration was expressed at population level with local communities and populations at risk. If this indeed represents a high quality collaboration niche, this is an insight worth deepening and systematizing in the future developments of the DEPP learning cycle.

In summary, what have we learned?

We are looking at those special places where collaboration is so good that it builds mutual capacities. To understand how those niches are developing, we need to:

- - Develop level 4 collaboration between learning processes at work in the DEPP

- - Spot where the humanitarian system has potential for more plasticity and inclusion

- - Identify innovative managerial approaches more satisfying locally

- - Understand better the contextual enablers of consistent collaboration

- - Strategically foster collaboration between local partners

- - Strengthen focus on the essential: local populations at risk.

And a temporary conclusion Quoting Kerouac's:

Waiting for the leaves to fall. There goes one!