Change maker: Faster and early action

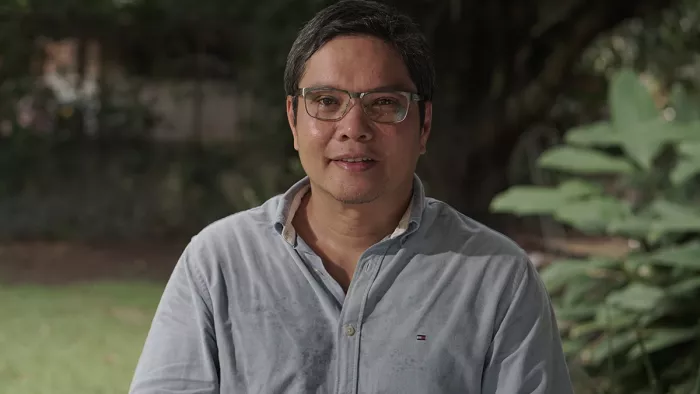

Alfredo Mahar Lagmay, University of the Philippines Resilience Institute/NOAH Center / Philippines (Manila)

My name is Alfredo Mahar Lagmay. I am a professor at the University of the Philippines National Institute of Geological Sciences and at the same time, I am also the executive director of the University of the Philippines Resilience Institute with the Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazards as its core component. My role, here in the Philippines, is to lead, as I like to call it or develop an army of Disaster Scientists.

I am a change maker for the faster and early action category.

I took my PhD degree in the field of volcanology. So, technically, I am a volcanologist, so I study explosive eruptions and included in that kind of work is the work on the assessment of volcanic hazards. We have about 300 volcanoes in the Philippines, about 23 are active and 27 are potentially active. We study volcanoes because there are other hazards that affect Filipinos in our country, for example, typhoons, for example, floods brought about by typhoons, strong winds. We have storm surges, we have landslide triggered by heavy rainfall and we also have earthquakes and the reason why we have all of these hazards is because the Philippines is situated in the Pacific Ring of Fire and also, we are along the typhoon belts.

So, there is really a lot of hazards that are constant threats to Filipinos and there have been many disasters that have affected, that have happened in the Philippines. Year after year, there’s probably about one or two disasters and in each and every disaster, there are many deaths—hundreds to thousands of Filipinos dying and since we have been having a lot of these disasters, we saw the need to build an army of disaster scientists.

We have a natural laboratory in the Philippines, each and every time there is a disaster, there is an opportunity to learn the lessons from those disasters and the basic objective or real objective is to be able to identify them, teach them to everybody and make it, if it’s possible, to be included in science-based policy decisions so that we do not repeat the same mistakes. But of course, you know that it’s not that simple. Many people forget we don’t remember the lessons, we don’t remember disasters after some time because they keep on moving from one place to another and the Philippines is a big piece of land, it is 300 thousand square kilometres.

So, my job is to document all of those lessons that have been learned or can be learned from those disasters, put it into that body of knowledge, educate as many people as possible down at the ground level and at the same time, influence policy decisions as well as introduce new ways of battling or avoiding the same hazards with the minimal cost possible.

When you plan, that is the quintessential early action. The preparation must come long in advance and the preparation must be laid out in a map, it must be laid out in documents, proper plans of what every individual should do during a disaster and how to be able to address it, nip it in the bud so that you don’t try to address those things you don’t need to address anymore because you planned well and I think this is the true meaning of early action.

You make use of technologies as well to help you out in the planning process, technologies that will help you to gather more data so that you can plan better. That, I believe is the main sense of early action. Planning ahead, preparing long in advance rather than just taking steps to know what to do during the actual hazard event or the actual disaster. Because if you prepare long in advance, you are avoiding a lot of things that are unnecessary to take care of during the hazard event or actual disaster.

I am a strong advocate for open data. Open data means, if you create something, you collect data, you share it on the web in a digital format that is easy to use, compatible with other platforms and available for both downloads without restrictions. All of that data needs to be available to people. Real early action has something to do with the planning of communities and when you plan, you have to plan it across all sectors.

I don’t think the hazards will stop because they are natural. What is not natural are disasters because they are a result of poor planning. That means you did not collect enough data, did not process the data, you did not find out the hazards based on that data, the hazards that are present in those areas, and if you are not ready because you did not plan, then a disaster will happen. A disaster is really a failure to anticipate the impacts of the hazards.

In the future, it would be a failure to anticipate climate change impacts. So as early as now, we have to make all of those preparations, all of these plans documented and well organised. Yes, I believe the hazards will always be there, but disasters may disappear because people will not be in harm’s way or if they are still in harm’s way (even with proper planning because you really don’t know how disasters will unfold) if they are still affected, it's minimal, it wouldn’t be worse if you did not plan for it. Where would [I] see our work to be in the next 10 years? We don’t really know because when you plant a seed, there is always this probability, there is a chance that it will grow and I believe that if you plant more seeds, these seeds representing ideas or the way things need to be done.

So, in many years, those writings and ideas that you introduced like:

Building an army of disaster scientists.

- Raising awareness through scientific discussions in radio programs.

- Like use of local technologies that would densify the network of sensors all over the Philippines, that would allow us to collect more information.

- Use of real-time data, the use of lidar, advanced technologies to model scenarios of floods, of landslides, of tsunamis or storm surges bigger than the hazards that we have experienced or remember. When you introduce all of these concepts, they may not be embraced now but they may be embraced later on. In that sense, I do not know where it will really end up, but I believe also that it requires patience. Whatever you introduce, all the things I have mentioned and more will be carried up and taken up by others and hopefully, they will become mainstream in disaster risk reduction and management in our country and hopefully in the world.

This article is based on an interview conducted by A Good Day in Africa. Listen to the full interview below.