We spoke to Dr Erica Thompson from the London School of Economics about her work with Start Network on anticipating crises.

Dr Erica Thompson has been working with the Start Network over the past few years to provide scientific expertise related to modelling forecasts of weather-related crisis. Through this work, the Start Network was able to establish an operational understanding about raising anticipatory alerts for heatwaves in Pakistan which helped support Alert 237. Erica is part of the Centre for Analysis of Time Series (CATS) at the London School of Economics (LSE) and agreed to be interviewed as part of our February theme around early action.

Can you tell us something about the work that you do?

I have a background in maths and physics and my primary area of interest is in the use of information from models: establishing the foundations of a model, looking at ways in which model output can be interpreted and how to improve the models based on the outputs we obtain. I have a PhD in climate change science and a particular interest in climate and weather models. The team I work in at the Centre for Analysis of Time Series are interested in a whole range of models: from ecological models of reindeer populations to financial models and even models which predict the outcome of sporting events. The methods we use are generalisable to almost any kind of model, but my particular interest is in weather and climate.

Can you tell us about your work with the Start Network?

Our interaction first came about through conversations between our Director Lenny Smith and the then Head of Anticipation at the Start Network Luke Caley. The motivation from our side was to be able to make use of the mathematical work that we are doing in a practical way - making anticipation work and doing research that people listen to. In 2017, we were able to secure funding from NERC to work on two projects: “Weather Information for Disaster Anticipation”, and “Improving the Role of Information Systems in Disaster Risk Reduction”. This enabled us to formalise our collaboration.

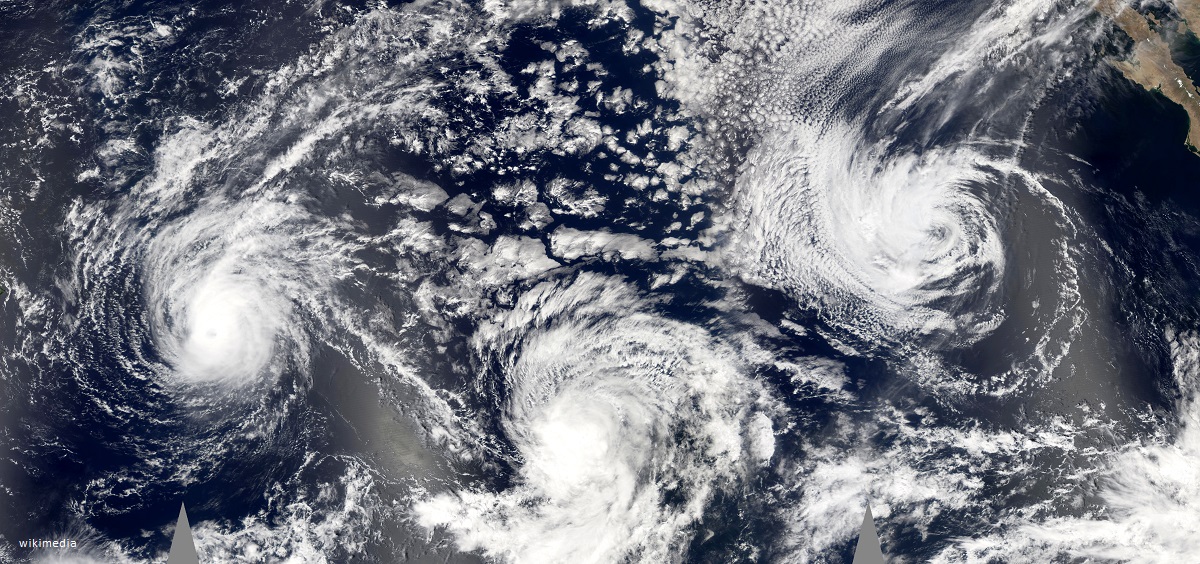

I have been working on improving the guidance for heatwave and cyclone hazards, as well as working specifically on anticipation of heatwave in Pakistan and cyclone in the Philippines. I have also been helping to assess alerts by checking the quality of weather-related information, where available. We have some really interesting questions at the moment about cyclone in particular, as the quality of the forecasts continues to improve. There is a clear opportunity for anticipation in some circumstances, but still a lot of operational questions about how best to do that and what level of confidence we need.

Our working relationship with the Start Network has been informal and very collaborative with frequent interactions to regroup, assess the outputs and find out what people on the ground think. For example, we had a webinar for the Pakistan heatwave product to establish what forms of information would be most useful for those who would be using this to make decisions. Rather than the standard academic collaboration which often involves passing on a research question and then a few months later having an academic paper thrown back over the fence, we have tried to keep the communication channels open to ensure we get the best and more useful product.

Can you tell us why you think it is important to have these types of collaborations between academics and organisations such as the Start Network?

There is value on both sides.

I find it personally very satisfying to see that my work is useful for other people. That I am not just in an ivory tower but producing work that is relevant. From the viewpoint of the University and the public funding I receive, it is important to establish the impact, and the work I have been doing with the Start Network is a great example of science having a real impact in society.

I also think it is useful for the Start Network to have these types of collaborations with academic institutions. If you are coming from a non-academic background it can be difficult to assess the quality of the wealth of information that is available to you. As academics, we can help point people in the right direction for high-quality information and explain what lies behind some of the data that they may want to feed into decision-making.

Looking to the future, where do you think the Start Network should be going with their early action work?

I have a number of reflections.

It has been really interesting to see the different approaches to early action by the Start Network and the Red Cross. The Start Network with its flexible and personal approach to activations, and the Red Cross with a more quantitative trigger-based methodology. The challenge now is to learn from each other’s experiences while separately maintaining the unique and important strengths of both.

It would be useful to develop a framework to house critical information on the models’ forecasting abilities and lead times for different crisis types. For example, one would start first by identifying where there might be humanitarian vulnerability, what types of events they may be vulnerable to, then the quality of the available possible models and the likely lead time – is it 10 days, 24 hours, or none at all? – and then cross-reference this with what actions could be taken in that time period. For the flexible approach adopted for the Start Network, those timelines are critical which is why these databases are so important. When there is an alert coming in, we want to be able to assess how far in advance can we accurately forecast – how good is the model? Can we rely on the forecast and take early action confidently, or not?

So, we initially focused on heatwave because it was expected to have good predictability, and in a sense, it is a “smooth” event. In other words, even if you miss a heatwave it will probably still be a very hot day and the actions you take will still have a marginal impact. However, more complex events like flooding are more difficult to predict and if they do not happen it is more likely that the actions you take will become a wasted effort.

It also depends on what you focus on in terms of crisis and actions. For example, if you focus on the effects of destructive winds in a cyclone, this is very sensitive to where it hits the coastline and any specific actions against this may be wasted if the exact area of landfall is incorrect. However, if you focus on the impact of the rain rather than the wind damage, then the impact will be across a larger geographical area, so high precision on where it hits the coastline is not so important.

Although it is easier to look at weather because there is more data, there is also an existing model base for epidemics. In principle, these could be forecasted and assessed in terms of the confidence that they will happen. The problem is the lack of data, so the confidence will be very low – but for a high-impact event that might still justify action.

This feels like a really exciting area to be involved with at the moment, with lots of potential for improving the way that humanitarians use forecasts and maybe even the way that forecasts are generated. I am looking forward to continuing to work with Start and other colleagues.

To read more about the work that Erica does at LSE there is a recent article she has published entitled Escape from model-land.

Learn more about Anticipation and Risk Financing.