Start Network's Localisation Framework has been updated in 2021 and is available to view here.

In advance of the launch of The Start Fund, Start Network and Localisation, a review into how Start Network programmes are faring on the localisation agenda, Start Network's David Jones discusses the issues around creating a holistic approach to localisation.

Donors and agencies agree: localisation is the future. What remains challenging is what that looks like. What actually is localisation? And how do we reach this aspiration? Critically, the humanitarian system is struggling with how we contribute to a shift of power and agency from the global north, southwards; from distance to proximity. The old adage that all development and humanitarian professionals must aspire for their own redundancy appears pertinent once more.

The ultimate goal is clear: local and national responders are, in most situations, the best placed to respond quickly and appropriately. In the situations in which they are not best placed, resource, infrastructure and other attributes usually associated with northern INGOs, are the differentiating factor. Resultantly, empowering local and national responders with capacity building and access to funding is key. The method of getting there – and navigating the barriers to doing so - is where the challenge lies.

The Grand Bargain recognises the importance of improved and increased funding for local and national responders, the need for institutional capacity building and, in forging strong partnerships. The Start Network is investing in capacity building programmes, principally through various DEPP (Disasters and Emergencies Preparedness Programme) projects, and the Start Fund has also been seen to promote the localisation agenda, not least through this year’s advent of the first National Start Fund, in Bangladesh.

Looking to the international Start Fund, there is further evidence of progress on localisation. In the latter part of 2016, the Fund experimented with a new reporting template to garner more granular information about interactions with partners. The results were impressive. Across a sample of 40 projects at the end of 2016, it was found that 62% of funding was disbursed to/through partners, representing 43% of the total amount awarded by the Fund. In the Start Fund’s third year, 64% of all projects involved partnerships. The statistics begin to paint a very positive picture, however it is critical to look beyond these initial figures, as promising as they are.

Localisation is an inherently far reaching, transformational and political agenda. Each aspect must be understood to avoid a shallow resignation of minor progress. To embrace such ambition, the Start Fund commissioned an external review of its practices in relation to localisation. Seeking a critical and constructive perspective, it found both strength and opportunity within the Start Fund mechanism.

The review cited a real strength in terms of what it describes as decentralisation. The Start Fund is clearly making great progress with the decentralisation of decision-making, with 88% of project selection meetings occurring in country and a further 12% based in the region. Its initiation of the Bangladesh National Start Fund is further progress still: a mechanism funded, managed and implemented solely in Bangladesh. The creation of structures and processes alone may underpin localisation, however it does not encompass it entirely. The review highlights the difference between a ‘technical-operational’ shift to a transformative one: engagement with capacity building, power dynamics and building strong national capacities and leadership.

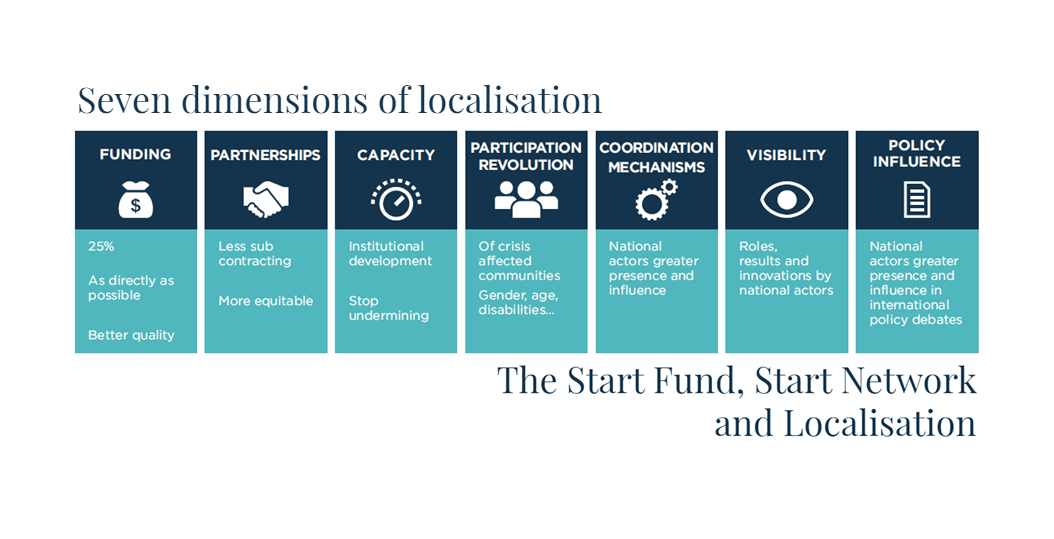

Specifically, the review defines seven key dimensions, each providing a critical facet to both decentralised and transformative localisation. They are:

- The quality and quantity of funding

- The equity of partnerships and relationships

- The participation revolution and the influence of affected populations

- The visibility of local and national actors in humanitarian and public spheres

- Engagement with national coordination mechanisms

- Capacity building, institutional and individual

- The influence of national actors on international policy

This perspective leads us to consider whether 43% of Start Funding going to partners is as positive as we think, especially if the funding simply covers specific activities? Could leaving partner agencies without financing for central costs lead them to incur greater risk from acting? Whilst there have been numerous efforts to drive transparency to donors and headway made with regards to affected population accountability, to what degree are there clear, transparent agreements between INGOs and their national or local partners? Are these partners and partnerships even clearly defined? Are all actors equitably represented to donors and in public spheres?

The reality is that there are examples throughout the spectrum. There are also times whereby funding-for-activities, for example, may be beneficial to partner organisations. However, what becomes clear is that there is a greater need for definition and specificity, for core principles to be articulated and implemented to ensure transparency and equity within partnerships, whether long term or fleeting. A critical ingredient lies in being able to understand the detail, to provide and analyse evidence to further investigate the complex and idiosyncratic relationships within the humanitarian system. The Start Fund is committed to doing so, however there will likely be barriers to the use of such insight. If there is unilateral engagement in the principles of localisation, what might the hesitations be, on an operational level?

Time constraints, efficiency and capacity (for example) represent a chicken-and-egg scenario. If there are concerns about the capacity of local and national responders, INGOs must surely engage in greater and more effective capacity building. Like localisation itself, capacity building has been an explicit goal and activity for some time. We must ask questions of how and why efforts have still led to such gaps. The first step, as ever, is understanding the problems in play and ideally understanding them in their fullness, their complexity. By recognising the dynamics of power - political and self-interest - we can begin to openly and honestly challenge the barriers to localisation. In refining and specifying what localisation really means, we begin to forge a clearer future. The next step to unleashing the potential of the humanitarian system is to localise it. To do so, we need a comprehensive and self-critical lens to embolden this ambitious vision.

Read more about the Disasters and Emergencies Preparedness Programme.

Read more about the Start Fund.

Download The Start Fund, Start Network and Localisation full report.

Download The Start Fund, Start Network and Localisation Executive Summary.

Read the Start Network Management Response to the localisation review.